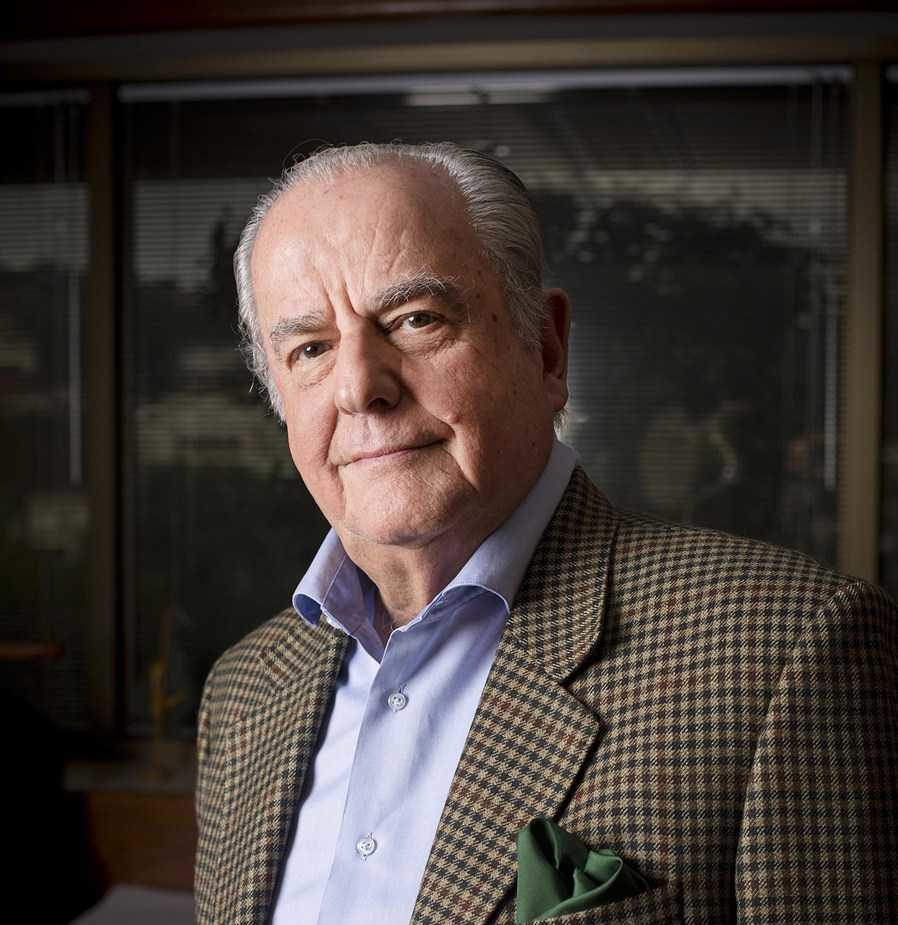

Interview with Roberto Teixeira da Costa: “We Should Remain Vigilant”

The first chairman of the Brazilian Securities and Exchange Commission (CVM), Roberto Teixeira da Costa, is a veteran but remains fully active as a thought leader. In an exclusive interview with Amec Viewpoint, the board member of the Brazilian Center for International Relations (CEBRI) analyses the ongoing situation of the capital market and draws comparisons with several other historical moments he experienced. “We should remain vigilant” is one of the statements made by the executive regarding the role of investors and Amec in terms of the companies’ governance practices.

At a time when several initial public offerings (IPOs) are on the rise, Mr. Teixeira da Costa emphasizes the role of Brazilian minority shareholders, especially in a setting where international investors are away from the Brazilian stock market. “International investors’ share (in the volume of transactions) has diminished recently. It is not like it happened from 2004 to 2008 when institutional investors took part in 60% to 70% of IPOs,” he said during the interview.

His most recent book, “O Brasil tem medo do mundo? Ou o mundo tem medo do Brasil?” (Noeses) — “Is Brazil Afraid Of The World? Or Is The World Afraid of Brazil?” in a free translation — addresses the difficulties of inserting the country in the international context. With a forward-looking approach, Mr. Teixeira da Costa says “Brazil can be saved”, despite the current challenges (article published in the Valor Econômico newspaper on July 9), in a nod to Pope Francis’ recent remarks, saying there was no salvation for Brazilians. Read the full interview below;

How do you see the evolution of the Brazilian capital market over time?

How do you see the evolution of the Brazilian capital market over time?

For those, like me, who have dedicated a lifetime to the development of the market, it is very satisfying to see we are living in a prosperous moment. The market’s goal is to mobilize resources so companies can grow, generating wealth and jobs. We have had several cycles over my 50-year career. There have been cycles that went back and forth, some happier moments and some crises.

Speaking of crises, what were the most challenging moments for our markets?

The biggest of all crises happened in the late 1960s. I call it “encilhamento” ( which literally means saddling-up[1]) and it lasted until 1975. This crisis led to all structural changes with the creation of CVM and the approval of the current Corporate Law (Lei das S.As), the institutionalization of the market, and more participation of international investors. From 1966 to 1971 several wrongdoings happened and we realized the market was not ready for healthy growth. The corporate law back then was outdated and did not bring incentives to foreign investors.

Another serious issue for the stock market was the competition with sovereign bonds that delivered a profit way above the market. There were times when interest rates were 14% above inflation. Sovereign bonds offered safety, warranties, and liquidity. The market was dormant for a really long time; there were a few offers but they were not very significant.

This has changed a lot in the past few years, hasn’t it?

Things started to change in recent years, I’d say since 2016, but especially in 2018 and 2019, when lower inflation levels led to lower interest rates in Brazil, allowing healthier competition with the stock market. The markets for private credit and real estate funds also benefited from it. Investors were quite spoiled due to income from the sovereign bonds.

Isn’t it a contradiction that the market is developing and thriving amid a pandemic and economic crisis?

It’s indeed a curious phenomenon. With the pandemic, all problems have become more visible. How will the stock market thrive? How can you draw projections for the future in a moment with so many casualties, when so many companies faced disruptions, etc. Surprisingly, the market managed to overcome all that. It is as if there were two separate scenarios: the sanitary front and securities.

Throughout its history, Amec has been working to strengthen governance best practices and to defend minority shareholders. How do you evaluate the association’s role in the current scenario?

Amec has been a responsible steward, ensuring governance standards are continuously improved. It is a constant fight. We cannot let our guard down. In times of euphoria, people buy what they are offered. Only a few care to proceed with a deeper analysis of the company’s fundamentals. When I worked as a consultant for companies, if they told me “I want to fundraise to fix my passives”, I would say “look, I think we started off on the wrong foot” and explained to them it wasn’t that simple. To go public means letting go of a family company approach to coordinate the interest of a set of shareholders that do not necessarily agree with the controlling shareholders.

And governance issues keep on happening, don’t they?

We constantly need to improve governance because people have an inexhaustible ability to find shortcuts. We should remain vigilant. Historically, governance advances in Brazil came as part of the market’s opening to foreigners. International investors were the main responsible for such advances because they wanted to have similar governance standards to what they had abroad. And companies have been adapting to such demands. Still, institutional investors have been participating less in the local market, unlike the 2004-2008 IPO boom, when international investors subscribed to 60% to 70% of IPOs.

Could you comment on CVM’s current structure?

I recently spoke with Marcelo Barbosa [CVM’s current chairman] and he told me CVM was not allowed to open hirings. He has been working with BNDES technicians who are available. So, Amec also has a very relevant role in demanding CVM is better equipped, with good, well-paid professionals in their staff. There is constant competition with the market.

What’s your view on the autarchy’s enforcement practices?

This is another demand that I often highlight. The time between the cause – including the probe, administrative process, and trial – until the sanction, should be the minimum. We all have short memories. Sometimes the moment is so nice that no one wants to remember that so-and-so has had improper behaviors.

Which sanctioning model should CVM adopt?

I have been to the United States once, visiting Stanley Sporkin, who was responsible for enforcement practices at the USA’s Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). There was a miner’s prospect on his table, full of red flags. I noted: “Stanley, don’t you think that this company should not be able to go public?”. He said: “Roberto, it is not up to us to make this decision, it is up to the investors. We cannot baby-sit investors.” And I replied: “but I see lots of red flags!”, to which he said “what matters is the buyers are seeing it”. CVM cannot replace investors. It should push to provide them with good quality information. Investors must have financial education. We learn from our mistakes. Those who have never made a mistake did not learn.

Could you talk about your most recent book, “O Brasil tem medo do mundo? Ou o mundo tem medo do Brasil“?

When I left CVM in 1980, I began to work in the Investors Relations area, first as a board member representing businesspeople in Latin America, then as a founder of the Brazilian Center for International Relations (CEBRI). Later, ( I founded) the Foro Iberoamerica with a team of journalists and businesspeople. I am also part of the University of São Paulo’s Grupo de Conjuntura Internacional. And last but not least, I am finishing my fourth tenure at the Inter-American Dialogue. All of this gave me extensive experience in international relations. I thought I might contribute to the field with my experiences and learning.

What are the book’s main ideas?

The thesis goes as follows: Brazil does not give international insertion the proper credit. We look a lot inside of ourselves. We overprotect our market. Our economy is still very closed. Businesspeople have no interest in taking part in international meetings and organisms. It’s rare. Boards rarely work on international issues. You can’t be like this anymore. The world is nearly knocking us down. The book was finished by the end of 2019. Then, the pandemic struck and Joe Biden became the US president. I almost had to rewrite the book. It is a massive transition. The pandemic has stirred markets here and abroad. The book was ready and the title was “Is Brazil afraid of the world?”. But, since then, the pandemic happened, deforestation reached new records in the Amazon forest, and a troubled political environment took a toll on the government, so I had to add to the title “Or Is The World Afraid of Brazil?”.

Despite the challenges, do you see a good outlook for the country?

Yes. I’d like to quote an article I recently published in the newspaper Valor Econômico called “Brazil Can be Saved”. I just was pretty shocked with Pope Francis’ remarks, saying there is no salvation for us. Yes, there is. We are the salvation, not Joe Biden, not (Vladimir) Putin, not Xi Jinping. We are the salvation, we have good brains in Brazil. Two years ago I traveled to Silicon Valley and I was impressed with the amount of Brazilians with companies and startups there. And I have asked some of them “why don’t you go back to Brazil?” and several of them said: “We are waiting for the best moment.” I’ve never seen so many entrepreneurs, so many startups in the country as we have now. I like to see our history as a movie. Right now, we are living through a worse drama than Gabriel García Márquez’s novels, but we’ll get over it.

[1] it refers to a chain reaction of financial difficulties